The highest learning outcome you can achieve from music theory is being able to compose pieces or scores that other musicians can read and perform. If you want to pursue music education at its highest levels, you can study theory, composition, or the science of music at universities that offer such graduate programs. Reading music is a common denominator of these programs, and this includes the ability to read ledger lines.

There are numerous elements of music theory; many of them are abstract concepts that the Prodigies programs introduce from an early age in order to set children on the right path to understanding music beyond its social aspects. Parents do not know if their children will one day become accomplished musicians, skilled performers, producers, or simply passionate fans who learned to love music through the education they received early on in their lives. Children who enjoy Prodigies Music programs and show enthusiasm as they progress through the levels will find it easier to tackle music notation topics such as ledger lines, which can be a bit mystifying even to those who read sheet music on a regular basis.

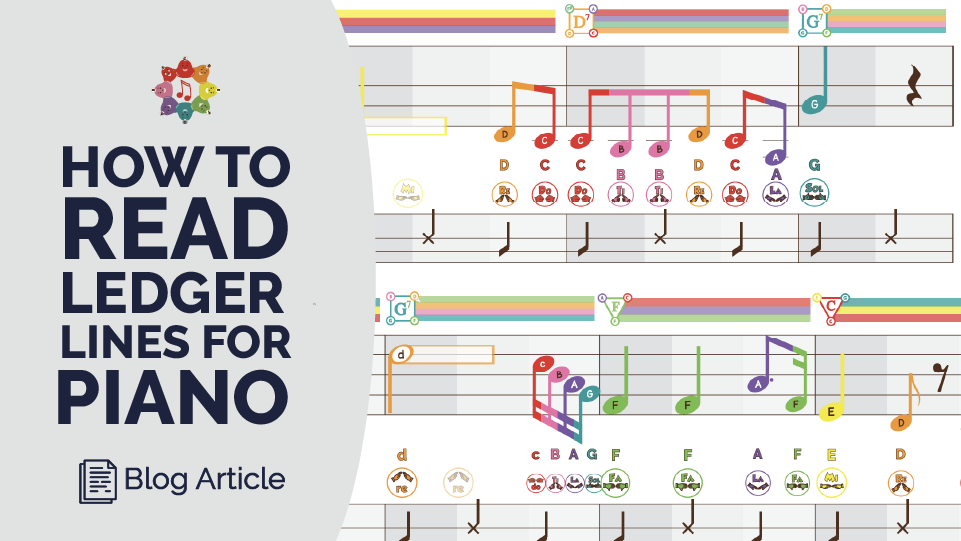

Reading music scores is not an easy subject to learn. It is just as much of a challenge to learn how to read music as it is learning to play certain instruments. Our goal is to introduce students to sheet music and notation as early as possible; to this effect, we rely on the color-coded method known as Chromanotes, which can be directly played on our Desk Bells. All the same, this is a tacit introduction to the piano, and all music educators know that sheet music and piano lessons are an excellent combination in terms of grasping, retaining, and eventually mastering music theory.

Before we get to the topic of ledger lines, let’s review the main elements found in music notation as they are written in a line. Each element is written from the bottom of the line upward, left to right:

- Pitch

- Time

- Meter

- Dynamics

- Articulation

There is another set of elements that are also written from the top to the bottom of the line and from left to right. They are meant to be used when reading or writing the actual score:

- Clef

- Key signature

- Accidentals

- Tempo

- Note heads

- Ledger lines

Standard sheet music for piano provides composers with five lines, but we can arrange notes in the spaces found between, above, and below these lines. We get a total of 11 spots where we can place notes, and then we have the ledger lines in case we are in need of an extension. Ledger lines can go up or down, and they can be used to indicate the width of notes.

What Composers Can Do With Ledger Lines

In 2018, a previously lost John Coltrane album was released by Impulse! Records. Originally recorded in 1963, “Both Directions at Once” is an album that makes a direct reference to Coltrane’s legendary love of ledger lines. As a composer and performer, Coltrane applied a mathematical approach to music; he believed that ledger lines could be as infinite as integers, which we know can flow in positive and negative directions, and this is how he envisioned music could be written. This gives you an idea of why reading ledger lines can be tricky at times.

Needless to say, your understanding of ledger lines will be dictated by your proficiency in reading basic staff lines and connecting them to your fingers as you play the piano. On albums such as “A Love Supreme,” it is hard to tell how many ledger lines Coltrane applied to his improvisational saxophone parts; prior to this album, however, he was mostly influenced by blues, so he kept ledger lines to about four. In the studio, Coltrane walked his musicians through the sheet music he composed because he knew that they would need to memorize the ledger lines.

Playing Ledger Lines by Memory

A very basic way of looking at ledger lines is that they represent specific pitches or intervals. An A can be played either as the A clef, or the G clef. Both are equivalent in terms of sounding the note. Coltrane’s piano man McCoy Tyner was methodical in his playing; he counted each note as it went in the direction intended by the jazz master. In other words, Tyner counted the lines separating the staff from the ledger, which happens to be the most basic memorization method.

As to how Tyner was able to make his fingers fly when performing with Coltrane using this basic counting method, let’s just say he is remembered as being one of the best jazz keyboard players of all time. You may think that this counting and memorizing technique is slow and tedious, but Tyner never had a problem with this. You can memorize just about any piece of music by counting through the score from the bass clef, and then back to the treble clef. The only things you have to remember are the number of notes between the clefs.

In some instances, though, a piano player does not want to memorize the ledger lines. If the piece of music has a chord progression where a part changes to a different key, it may be that the ledger lines are no longer applicable. In this case, instead of counting, the pianist looks at the chord symbols and counts the number of lines needed to get to the chord. This can be very tedious, and in Coltrane’s case, would often mean the pianist would have to play it several times to make sure that he counted the lines correctly.

The next time you play a piece of music, try thinking about it in terms of how many ledger lines are needed, then count your way through.

Reading Ledger Lines for Bass and Treble Clefs

This method will likely feel more natural to Prodigies Music students because it takes advantage of music theory knowledge. Let’s say you are looking at a treble clef with the highest note being E. Since you already know the note scale, the logical progression would be F, G, A, B, C, D, E before getting to the ledger line at the top. A masterful player like McCoy Tyner can do this in a heartbeat while reading a score for the first time. The rest of us are better off skipping.

You can skip up or down when reading ledger notes for piano. You can even skip in both directions at once if you are able to understand music theory like Coltrane did. There is a trick for doing this, and it is very easy to remember: GDB FACE. To use it, you have to skip upwards from the landmark note so that you can go, for example, from high C to E if the ledger is on the line. When looking at ledger lines below the staff, the skipping goes down from the landmark note so that you can go, for example, from G to B. You can practice this method with GBD FACE on the line notes and FACE GDB on the space notes. It really works in both directions, but not at once.

Becoming Proficient in Reading Ledger Lines

Aside from GBD FACE, there is another mnemonic device you can use to speed up your reading of ledger lines, and it goes like this:

Every Good Boy Deserves Food

This device will work with treble clef notations; it reminds you of EGBDF for the purpose of stacking and skipping line notes quickly. With regard to space notes, you can just use FACE. You can come up with your own mnemonic devices if you wish; many piano players do so as students, and they stick to them throughout their performing years. The line notes on the bass clef are DEFGA, which could be expressed as:

Do Everything For Good Advice

For the space notes of the bass clef, DCBAG, you could use:

Don’t Come Before Another Goes

Reading ledger lines will not be the most difficult aspect of your piano lessons. Unless you come across avant-garde sheet music from composers far more progressive than Coltrane, you will rarely see more than four ledger lines above or below the staff. As with just about everything else related to piano lessons, practice makes perfect when it comes to memorizing ledger lines.